Critical Self-Reflection + Contemporary Art (Pt.2 of Critical Arts Pedagogy)

Originally Published in Art Education Journal, 74:5, 19-24, DOI: 10.1080/00043125.2021.1928468

Continued from Critical Arts Pedagogy: Nurturing Critical Consciousness & Self-Actualization through Art Education

Contemporary Art and Identity

Critical self-reflection, including understanding one’s multiple intersecting identities and their position within systems of power, is foundational to both ethnic studies education and antiracist identity work (Crenshaw, 2017; Sleeter & Zavala, 2020). Our final project leads students through some of this identity work, grounding them in their positionality and helping them recognize their own spaces of power, oppression, and privilege.

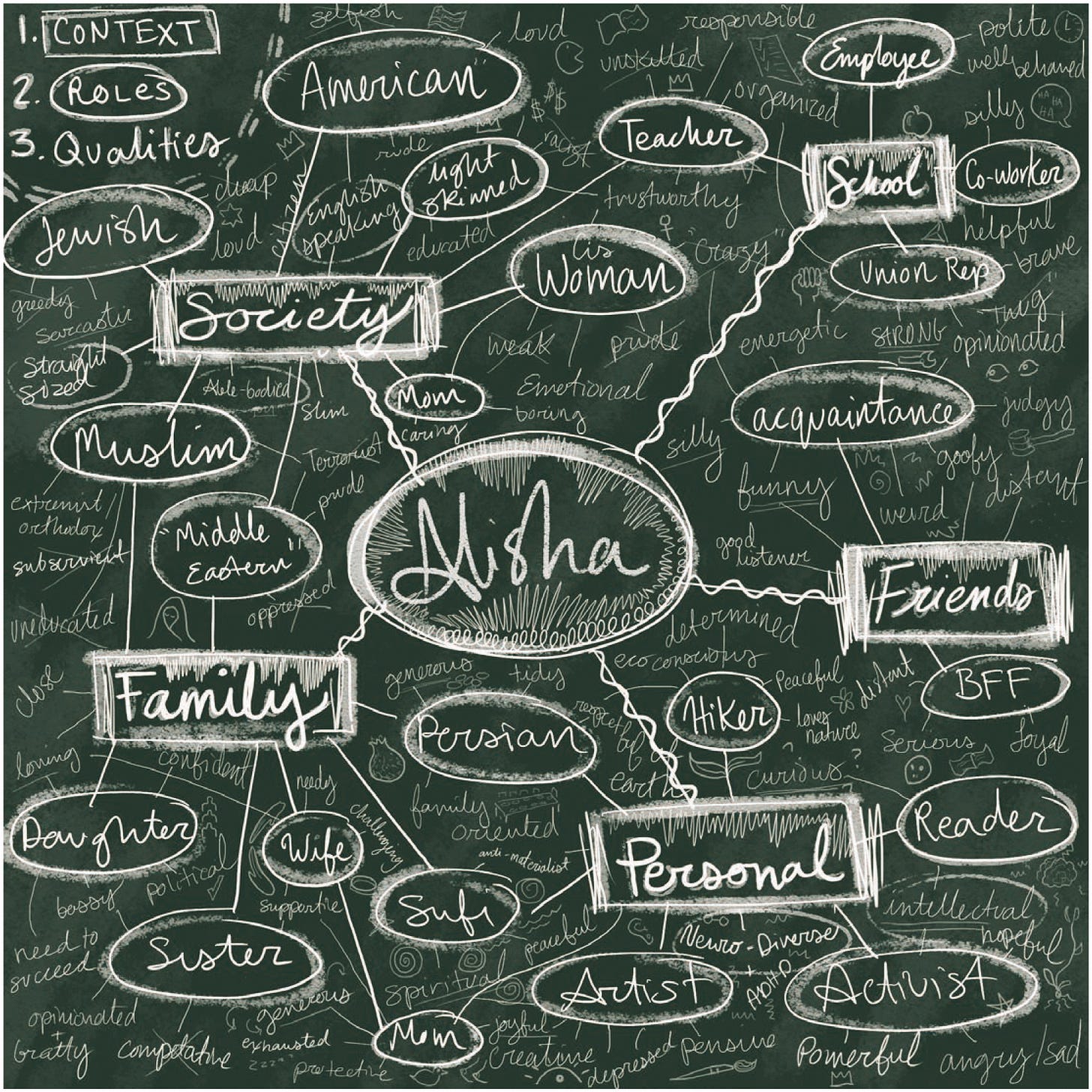

We begin this project with identity mapping. I stand at the front of the room—modeling the self-work and emotional poignancy I ask of them—as I map my own identities on the board (Figure 2). I begin with my name and five lines branching out to different contexts in my life: School, Family, Friends, Personal, and Society. “How many of you are a slightly different person when you are hanging with your friends than you are while visiting an elder in your family?” I ask. We laugh as the majority of the class raise their hands. This framing helps students recognize the way social context shapes identity and how each individual exists as multiple identities within different contexts.

Next, I name and list two to three roles that I play within each of the contexts listed. Under School, I write “teacher, employee, coworker.” Students follow along, completing their charts as we talk, writing “student, classmate, athlete”—whatever applies. Under Personal, I write “artist, intellectual, avid reader.” Under Family, I write “daughter, sister, Persian, Sufi.” When we get to Society, I ask students to help. “What should I write here? If you didn’t know me, what identities would you assume I hold?” Students hesitate, giggling, but eventually offer up, “Woman, 30-something, White? Vaguely ethnic?” I explain that, in some contexts, I pass as White, but in other environments I read as Middle Eastern: for instance, when I attended a primarily White institution for college, or when I am at the airport with my family, and we are “randomly selected” to have our bags searched.

Under each role, we add two to three qualities. As a sister, I am competitive and needy. As an artist, I am creative, spiritual, and obsessive. “What should I put for teacher?” I ask them. “Helpful, funny, weird, moody.” Fair enough. Next, they help expand on my roles in society—what qualities would strangers assume I have? Again, with hesitance and giggles, they volunteer adjectives to add to my map. Women are seen as weak, emotional, crazy. White people are assumed to be wealthy, racist, and shallow. Middle Eastern people are viewed as terrorists, conservative, and oppressed. Students continue to fill in their identity maps—how do they believe society views them? What stereotypes and biases are at play when we face the world? We work alongside each other, as I add to my map on the board: Illustrating, annotating, and writing notes to myself, I circle the characteristics most important to me, draw an X over qualities with which I disagree, crowns where I hold power or privilege, lines between similar concepts, and so on. In short, I process what I have just unpacked through visual annotations. Students do the same.

We spend our 2nd day examining a broad collection of contemporary artists who investigate identity through their work. I prepare an online gallery of artwork and articles, choosing artists carefully to include a broad range of topics and issues in identity. Students break into small groups, and each group enters into a dialogue about a single artist’s work—analyzing, interpreting, and debating what they will ultimately share with the class. Optional conversation prompts are on the board: “What is the hidden message? What does this artwork suggest about how identity is formed? What issues in identity are the artist exploring in their artwork? Make connections between this artwork and what you know about society or history.”

The presentations are profound—because students have been developing their critical consciousness throughout the year, they are well equipped to recognize the critical themes investigated by each artist. Students note the intentional centering of Blackness in Kerry James Marshall’s paintings, discuss issues of cultural appropriation and erasure brought up by James Luna’s performance pieces, and identify issues of representation in Lalla Essaydi’s self-portraits.

As students present, we take notes of the emerging common themes: race, gender, sexuality, immigration, religion, gentrification, assimilation, beauty standards, body image, family structure, and much more. At the end of the period, we have written on the board a long student-generated list of “issues in identity” explored in contemporary art.

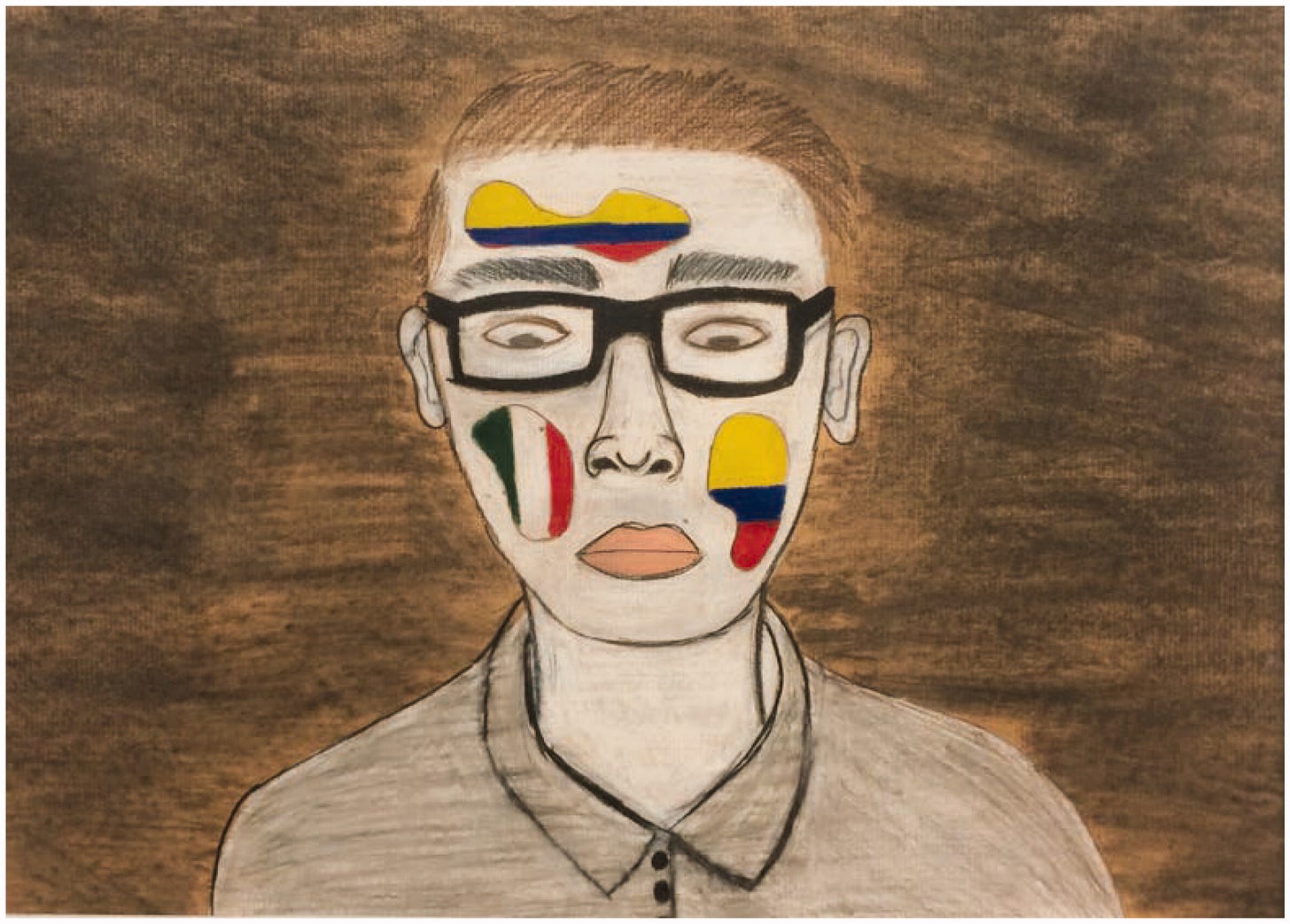

Finally, students begin drafting proposals for their artworks—which they will have 3 full weeks of studio time to create before a public exhibition. The only project criteria given is “make a statement, or ask a question, about identity.” Everything else—media, style, imagery—is all up to them. I have a variety of optional brainstorming activities, which I host in small groups, but most of the class hums with quiet conversation as students support each other and sketch out their ideas. At the end of the period, I collect their proposals and take the weekend to process student ideas, adding my own questions, connections, and suggestions.

Liberatory “Studio Time” and Community Learning

The next 3 weeks are filled with fluid, highly individuated, occasionally chaotic workdays. I run around the room facilitating peer feedback, pushing student thinking, suggesting materials to explore and artists to research. Each class begins with each student planning their objective for the day and ends with a formative mini-critique between peers. The level of peer communication is striking; because students have been developing their critical lens all year, they can now readily make poignant observations both about the design of each other’s work and the social topics explored.

At last, we hold an exhibition of our finished works (Figures 3–10). Our art classes meet in a makeshift gallery space and lead visiting classes on tours. Artists wear name tags, have written and rehearsed artist statements, and are prepared to answer questions about their work. Community members, school staff, district leadership, and local gallery and museum staff are also invited. The conversations I overhear at these exhibitions are genuinely the best part of my job. The final exhibition results from a year of careful scaffolding toward critical consciousness, confidence, and independent artmaking.

Critical Praxis and Reflections

While I am incredibly intentional about my lesson planning, the only way to truly measure my impact is by assessing for an enduring critical lens—in other words, I regularly ask alumni for feedback. Willingness to engage in a continual cycle of critical self-reflection and self-improvement toward our pedagogical goals is a core principle of critical pedagogy—called praxis (Freire, 1970). The concept of praxis is also relevant in personal antiracism work, in which self-knowledge is understood as merely the beginning of a lifelong critical reflective practice (Kendi, 2019; Lawrence & Tatum, 2004). Student feedback over the past decade has helped me identify and address critical gaps in my perception, especially regarding discipline policies, trans inclusivity, and Indigenizing my curriculum.

In good praxis, I recently asked alumni what they remembered of our class. Angélica, class of 2016, remembered it as the space in which she “grew a sociopolitical consciousness.” Daniela, class of 2018, remembers our final project as “very liberating” and that our final exhibition “made it very clear that art wasn’t all about sunshine and rainbows.… Art has the power to educate people.”

Jenny, class of 2019, reflected on classroom culture: “The word that comes to mind is community.… [S]tudents would cry because of how emotional their projects were, but because of the community built up over time in the classroom, everyone was very open and respected one another.” Similarly, Vanessa, class of 2014, recalled “feeling comfortable enough to share personal details about [her] life.”

This comfort, and the genuine culture of love and respect it represents, is an important reminder of the importance of establishing a safe space before facilitating critical dialogue. Asking students to explore social justice topics without a respectful class community can inadvertently cause more harm than good. This is especially true when asking students to represent themselves through art, as potentially traumatic feelings and memories may be unearthed through reflective artmaking. Students know they can be authentic in their final artworks because we have practiced respectful dialogue and community all year.

Ultimately, this is core to what I want students to take away from my classroom. I want students to know themselves well, have difficult conversations, understand their power, and use their identities as a launching point toward social consciousness and social action. I want them to self-actualize as critical citizens and freedom dream through their artwork, conspiring individually and in community to envision and create the world they want for themselves.

With a solid understanding of my critical purpose, an intentional but flexible curriculum design, and a continuous reflective praxis, I feel more and more effective as a critical arts pedagogue each year. As antiracist and social justice education become more mainstream, I hope educators will take a holistic approach in their classrooms, recognizing that critical consciousness and class culture are just as powerful as liberatory content (hooks, 1994). We must model our classrooms after the liberated world we wish to inhabit and focus every aspect of our planning and practice toward meeting that goal. ν

Notes on contributor

Alisha Mernick, Art Teacher, Gertz-Ressler High School in Los Angeles, California. Email: maynoush@gmail.com. Mernick is also CAEA Southern Area President-Elect and one of the CAEA ED&I Commissioners.

References

Acuff, J. B. (2018). “Being” a critical multicultural pedagogue in the art education classroom. Critical Studies in Education, 59(1), 35–53.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. New Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Cultural action and conscientization. Harvard Educational Review, 40(3), 452–477.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.; 30th anniversary ed.). Continuum. (Original work published 1970)

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World.

Lawrence, S. M., & Tatum, B. D. (2004). White educators as allies: Moving from awareness to action. In M. Fine, L. Weiss, L. P. Pruitt, & A. Burns (Eds.), Off white: Readings on power, privilege, and resistance (2nd ed.; pp. 362–372). Routledge.

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Miner, B. (2014). Taking multi-cultural, anti-racist education seriously. In W. Au (Ed.), Rethinking multicultural education: Teaching for racial and cultural justice (2nd ed., pp. 9–15). Rethinking Schools.

Sleeter, C. E., & Zavala, M. (2020). Transformative ethnic studies in schools: Curriculum, pedagogy, and research. Teachers College Press.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.